Anthony Liem wrote a text about the history of the Gamelan Digul, the first gamelan in Australia, which is an important historical object illustrating the fight for Indonesian independance against Dutch colonial rule. This gamelan is at display at the Monash University, Performing Arts Centre in Melbourne in the Margaret Kartomi Gallery.

After some 80 years after it was written by Ivens, a bound typoscript of his first autobiography The Camera and I, was found in Portland, Oregon, USA. Ella Thomas, who is for 32 years Director of Education for the Northwest Film Center, the Northwest region's largest and most comprehensive film arts organization, writes how she found it:

When watching Mstyslav Chernov’s Oscar-winning film 20 Days in Mariupol, Alex Vernon, professor in English and specialist in 20th century war-literature, could not but see parallels with The Spanish Earth. This documentary by Joris Ivens, John Fernhout and Ernest Hemingway was the result of 40 days of film shooting in besieged Madrid in 1937. Both films draws on personal footage with an harrowing account of civilians caught in the siege, in 1936 a new kind of warfare.

Read more: Oscar Winning '20 Days in Mariupol' (2023) and Ivens's '40 Days in Madrid' (1937)

The European Film Academy (EFA) honors Joris Ivens, The Bridge (1928) and the vertical-lift bridge in Rotterdam (Koningshaven Bridge) by including it as Treasures of European Film Culture. It is for the first time that a Dutch filmmaker and location is included in this growing list of in the meanwhile 49 European locations in 24 countries, which or of extreme importance for the European film culture. According to the EFA these places of historical value need to be maintained and protected not just now but also for generations to come.

Famous locations of this list are the great staircase in Odessa from Eisensteins’ Pantserkruizer Potemkin(1925), the Trevi Fontain in Rome (La Dolce Vita, 1960) and the Notting Hill Bookshop (Notting Hill, 1999) in Londen.

See: https://www.europeanfilmacademy.org/activity/koningshaven-bridge-rotterdam-netherlands/

With The Bridge Joris Ivens freed the filmcamera, because he brought to live a 'dead iron machine' without a fixed tripod, without a script, without actors, filming spontanously, climbing and performing break neck tricks on the beams of the lift bridge. This lift bridge was opened at the end of 1927 and within a few weeks Ivens alerasdy started filming with a Kinamo hand held 35 mm. film camera. This groundbrealing film presented The Netherlands as a new, modern country, no longer with the folkoristic images of wind mills and Volendam puff pants. This short film conquered immediately the avant-garde cinema theaters of Europe. With The Bridge Ivens became worldwide one of the pioneers of a new film language. He discovered himself during the editing the effects of rythm in film, of directions and movements, and called his film 'My Mondrian', with a game and balance of opposites. He also was amazed by the effects of perceptual psychology: it is possible to create a world on its own on the cinema screen. The simple narrative looked very realistic: a train from the south is arriving at the railbridge, but has to stop because the liftbridge opens for passing boats, and only after the bridge is closed again the train can continue its track to the north. It wasn't realistic, but an invented drama: ‘There is also such thing as a train timetable, preventing trains to stop', wrote the journal of train drivers. For Ivens this result was quintessential for the start of his film career. From that moment on he knew that he could create film art with a world on its own.

Joris Ivens (Nijmegen 1898-Parijs 1989) grew up in the family of Kees Ivens, an entrepreneur in photo equipment and his grandfather Wilhelm Ivens, a prolific photograper. In these three generations one can notice the for The Netherlands unique organic transformation from photography (the art of the 19th century) to film art (the art of the 20th century).

Since 1997 the Joris Ivens Archives are established in his birthplace Nijmegen which is managed by the European Foundation Joris Ivens in the Regionaal Archief Nijmegen.

Award and decorations Joris Ivens

1955 Ivens ontvangt de Wereld Vredesprijs in Helsinki.

1957 Wint een Gouden Palm op het filmfestival van Cannes en een Golden Gate Award in

San Francisco met de film La Seine a rencontré Paris (De Seine ontmoet Parijs).

1966 Zilveren Leeuw op filmfestival van Venetië voor Pour le Mistral

1967 Ontvangt de Internationale Lenin Prijs voor Wetenschap en Cultuur in Moskou.

1978 Het Royal College of Art in Londen verleent Ivens een ere-doctoraat.

1984 Wordt benoemd tot Commandeur van de Legion d`Honeur (Franse ridderorde) door

de Franse president Mitterand.

1985 Ontvangt Het Gouden Kalf (Hoofdprijs op het Nederlands Film Festival in Utrecht)

uitgereikt door minister Brinkman.

Wordt geridderd tot Groot Officier van de Republiek Italië.

Ontvangt de gouden medaille voor "grote verdiensten voor de Schone Kunsten" van de

Spaanse koning Juan Carlos.

1987 Ontvangt de "Che Guevarra Prijs" in Cuba.

1988 Krijgt uit handen van Gina Lolobrigida de Gouden Leeuw voor zijn gehele oeuvre op

het internationale filmfestival van Venetië.

Wordt door burgemeester Ien Dales benoemd tot ereburger van zijn geboortestad

Nijmegen.

1989 Wordt tot Ridder in de Orde van de Nederlandse Leeuw gedecoreerd door koningin

Beatrix.

Sterft in Parijs op 28 Juni.

Marceline Loridan-Ivens (zijn vrouw) wint een Felix ("de Europese Oscar") voor Ivens`

complete oeuvre en in het bijzonder voor de laatste film die ze samen maakten Une

Histoire de Vent (Het verhaal van de wind).

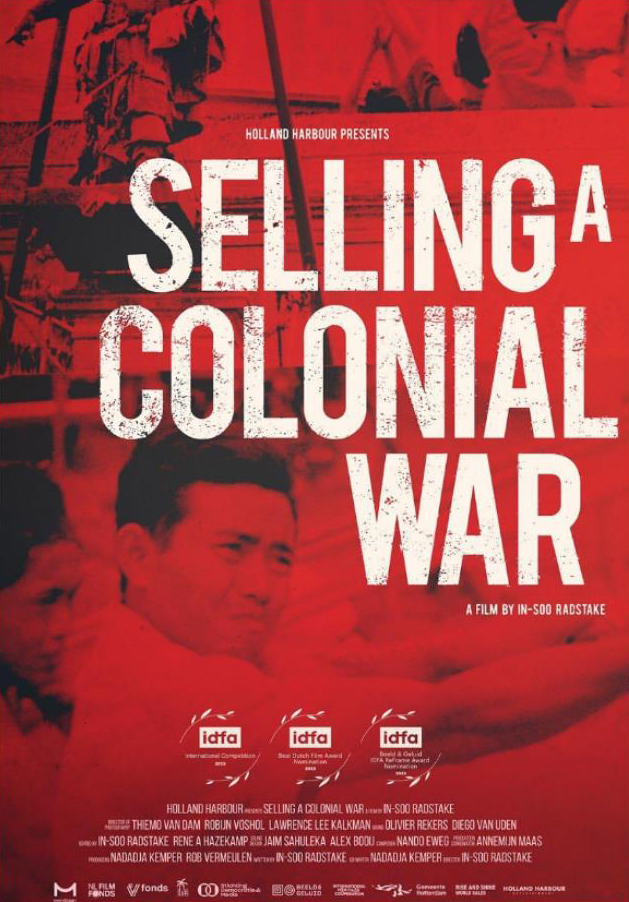

After Joris Ivens made Indonesia Calling (1946) he was immedialtely accused of anti-Dutch propapaganda. Officers of the Secret Service also immediately proposed to withdraw Ivens'passport. Not in 1951, but already in 1945. In a new documentary Selling a Colonial War filmmaker In-Soo Radstake casts a broad view of perpectives, among others a remarkable view of former Dutch minister of foreign affairs Ben Bot. He confirms that it was the Dutch government itself which used pure propaganda, censorship and concealing language to disinform or not inform at all what was really going on in Indonesia. Gerda Jansen Hendriks, a film historian and specialist in Dutch propgandafilms about the Indonesian fight for independence, states about Indonesia Calling : 'The controversy is actually not about the film itself. It is the person of Ivens. Conservative colonials wanted to take revenge on Ivens, becase he was regarded as a threat to their position.' Next to footage of Joris Ivens's film and an excerpt of an interveiw with him about the film also Anthony Liem is filmed. In Sydney he testifies of the support his father-in-law Fred Wong gave to the strike of the harbour workers and to the production of the film.

This splendid documentary provides an excellent oversight of the complex political and historical processes of the Dutch decolonisation process. Already in 1949 the Dutch government knew about the war crimes committed by the Dutch army. It was Cornelis van Rij, a former member of the resistance and lawyer, who investigated three exemples of such violent acts in 1949, but his clear juridical conclusions were covered by the government and not made public.

According to In-Soo Radstake everybody on both sides were victims, and suffered from pain and bitter disappointment. It is remarkable however that in the national debate, and also in this documentary, the highest political responsible figure of these war crimes, prime-president Louis Beel, is never mentioned. His nickname was not without reason 'the Sphynx'.

The film Sellling a Colonial War was premiered at IDFA and can now be seen in Dutch cinemas (January 2024).

The power of representation is demonstrated clearly in the way the Dutch government chose to present the Indonesian War of Independence and its violent aftermath (1945-1950). Three quarters of a century on, competing perceptions of the events still remain. Filmmaker In-Soo Radstake casts a broad view as he investigates a multitude of perspectives, including those of the Dutch government, servicemen in the Dutch and the Royal Netherlands East Indies armies, Indonesian independence fighters, the international community and several population groups in the former Dutch East Indies. The Bersiap killings, a neglected episode in which specific groups of citizens were collectively considered as enemies of the revolution, is among the subjects touched upon.

Extensive interviews with international experts provide insight in the complex relationships in the former colony and the global context. Archive footage—some of which has only been discovered decades after the events—not only tells a story of decolonization but also chronicles our dealings with the past.

The Second Stage production of Spain in the Tony Kiser Theater in New York presented in December '23 a play about The Spanish Earth with Joris Ivens, Helen van Dongen, Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos as the protagonists. Jen Silverman writes that Spain is not “a history play in the most conventional meaning.” It’s “set in 1936 in the West Village,” she says, then adds, “Sort of.” "This 90-minute comedy-drama is an absurdist-tinged fantasy that seizes a moment of history and bends it to the breaking point", she continues. And indeed it is: absurd.

Tony Kiser Theater, 305 West 43rd street

Was Joris Ivens a KGB spy or Helen van Dongen? No, they never were. But Stephen Koch in his fictionalized book about The Spanish Earth and the breaking point between Hemingway and Dos Passos claims this without evidence. Only the looks of Helen van Dongen were already enough to proof this claim, when Koch writes: '...she was just as smart and just as chic - a tricky mix of innocence and experience, small breasted, supple, and so sexy it was a little scary.' The typical looks of a spy, how appropriate, so she must be a spy! Koch clearly never met Helen van Dongen, his quite subjective and little scary description of her, opposites the observations of people who did meet her in real life. According to Koch even John Ferno - oh dear - must have been 'another Comintern appratchik'. John Fernhout must have been shocked by this stupid accusation. Was The Spanish Earth paid by Russian money? No, it wasn't, no penny. It was only paid by Contemporary Historians Inc., the USA intellectuals who raised money for this film with the aim to buy and send ambulances and medical equipment to support the elected democratic government. And they succeeded, the revenues of the distribution of the film were enough to get 17 ambulances to Spain. Ivens himself didn't earn any penny with this production, he was only compensated for his expenses.

So what is the sense of this comedy play? It fits the anti-intellectial climate ignoring facts and making a fool of sincere intentions of artists. This is comedy and at the same time also (s)painful fun.

The play is based on Stephen Kochs' book 'The Breaking Point', which is fictionalized history based on fictionalized fiction of Johan Dos Passos: his very subjective memories of 40 years after the historical events happened, posthumously published in 'Centurys Ebb' in 1975. His memories contain a truckload of proven mistakes, biased by his rightwing political beliefs at that time. A play based on fiction that is based on other fiction results in an absurd story which floats further and further away from what happened in reality. Indeed 'ahistoric' according to the director of the play. With so many contradictory voices and opinions it makes sense again to return to the art work itself and just watch The Spanish Earth and find out yourself.

This is what the creators of this play published on the website:

Jen Silverman’s Spain is inspired by a kernel of historical fact—just a kernel. It concerns a documentary, The Spanish Earth, calculated to rouse sympathy in the United States for Spain’s Second Republic in the long civil war against General Francisco Franco’s fascist insurgency. There was (or, rather, is) such a documentary, produced by Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens and American editor/producer Helen Van Dongen, released in 1937. A number of noteworthy American intellectuals worked on the film, including novelists Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos, playwright Lillian Hellman, actor Orson Welles, poet Archibald MacLeish, and composer Virgil Thomson. In stage directions, Silverman writes that Spain is not “a history play in the most conventional meaning.” It’s “set in 1936 in the West Village,” she says, then adds, “Sort of.” This 90-minute comedy-drama is an absurdist-tinged fantasy that seizes a moment of history and bends it to the breaking point.

Burnap engages with Danny Wolohan (left) as novelist Ernest Hemingway, whom everyone agrees “can be too much.”

ahistoric

Silverman's protagonist-antiheroes are Joris (Andrew Burnap) and Helen (Marin Ireland), self-proclaimed devotees of art, who have accepted Soviet financing for a documentary about wartime Spain and are operating under covert supervision by the KGB. Of the American intellectuals involved in creation of The Spanish Earth, only Hemingway (Danny Wolohan) and Dos Passos (Erik Lochtefeld) are included in the play. These two are famous for their love of Spain and its culture (bullfighting for Hemingway, villages and backroads for Dos Passos). Recruited as celebrity window-dressing, they’re inadvertently lending credibility to a questionable project. Karl (Zachary James), Joris’s KGB “handler,” insists the film should depict the political issues of the Spanish Civil War as straightforward. “War can get so complicated if you try to understand all the different bits” (such as “who did what to whom”), says Karl. “Keep it simple.” Keeping things “simple” means characterizing the war as a black and white conflict between rich and poor, with “the noble peasant crushed by the rich Fascist.” A single-sentence war, Karl contends, “is a perfect opportunity for … ART.” But Joris, narrating the play’s opening scene, cautions that “art” is not “the word [Karl] meant.” With the Roosevelt administration unwilling to intervene in Spain, the KGB aims to gin up U.S. support for the Spanish government as part of a much larger Soviet-Communist plan to deter fascism not only in Spain but throughout Europe. Erik Lochtefeld plays novelist John Dos Passos, recruited to participate in an antifascist documentary that aims to rouse American sympathies for the government side in the Spanish Civil War in Jen Silverman’s ahistorical comedy-drama Spain. On its silky, urbane surface, Spain appears, at first blush, primarily about the tension between art and propaganda. Silverman’s version of Hemingway says that, as a writer, “[y]ou get inside somebody’s brain and you rifle around and you change the connections, you change the neural pathways, and then you change them. And maybe? You save their life.” According to Hemingway, great writing—writing with integrity—is “radical brain surgery.” Helen describes propaganda as similar to that, but different: “the thoughts you have are … formed, shaped, designed to meet a set of specifications, and then served to you. You aren’t having a thought, you’re receiving the thought that someone else crafted for you.” The play’s documentarians are turning out propaganda because it seems clear to them that (as Helen puts it), in the Great Depression economy, “nobody was gonna let me make movies for a living” in any other way. They believe themselves to be in a bind comparable to current-day artists whose work is unsustainable in a society that’s besotted with pop-culture and disinclined to subsidize uncommercial creativity. At times, the cloak-and-dagger shenanigans of Silverman’s intellectuals and their Soviet contacts are reminiscent of digital meddlers in today’s political life. And in the final scene—a coda that lands out of the blue, confirming Silverman’s absurdist bona fides—it’s explicit that Joris, Helen, Hemingway, and Dos Passos are connected in the playwright’s imagination to personnel of Russian troll farms, skulking about cyberspace, spreading disinformation, interfering relentlessly in the civic life of the United States. Zachary James is Karl, the KGB “handler” who has solicited Joris and Helen to produce The Spanish Earth. Directed by Tyne Rafaeli with the melodramatic velocity of early Hollywood espionage dramas such as Watch on the Rhine, Spain barrels over the incongruities of Silverman’s script with hardly a noticeable bump. Using deep shadows, unexpected shifts of illumination, and a series of sliding panels, scenic designer Dane Laffrey and lighting designer Jen Schriever expertly create the atmosphere the playwright requests in her stage directions: “dangerous spy thriller, understated, not cheesy.” With a turntable for cinematic fluidity, the production appears relatively simple, but the creative team provides a myriad of striking details that lift the look and feel of it all far above the ordinary. Despite the presence of actors fully capable of grand star performances (especially, Ireland and Burnap), this first-rate cast is a sturdy ensemble that works together with the balance, rhythm, and mutual-support of Balanchine dancers.

During a concert at the 'Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy' University of Music and Theater in Leipzig the subject of Climate Change was íllustrated' by Ivens' film Rain/Regen (1929) accompanying Hanns Eisler’s "14 Arten den Regen zu beschreiben" (*Fourteen Ways to Describe Rain). In a packed great concert hall this magnificent performance became a marvellous highlight of the night. The musicians played with energy, joy and much competence. Hanns Eislers and Joris Ivens art works were much appreciated by the audience and critics as well.The initiative for this student project came from student Charlotte Steppes, who plays the piano in the "14 Arten den Regen zu beschreiben“.

Prof. Irmela Boßler - Flöte

Matthias Kreher -Klarinette

Semi Hong- Violine

Viola Wasser - Viola

Konstanze Pietschmann - Violoncello

Charlotte Steppes - Klavier

Prof. Christian Hornef - Dirigent

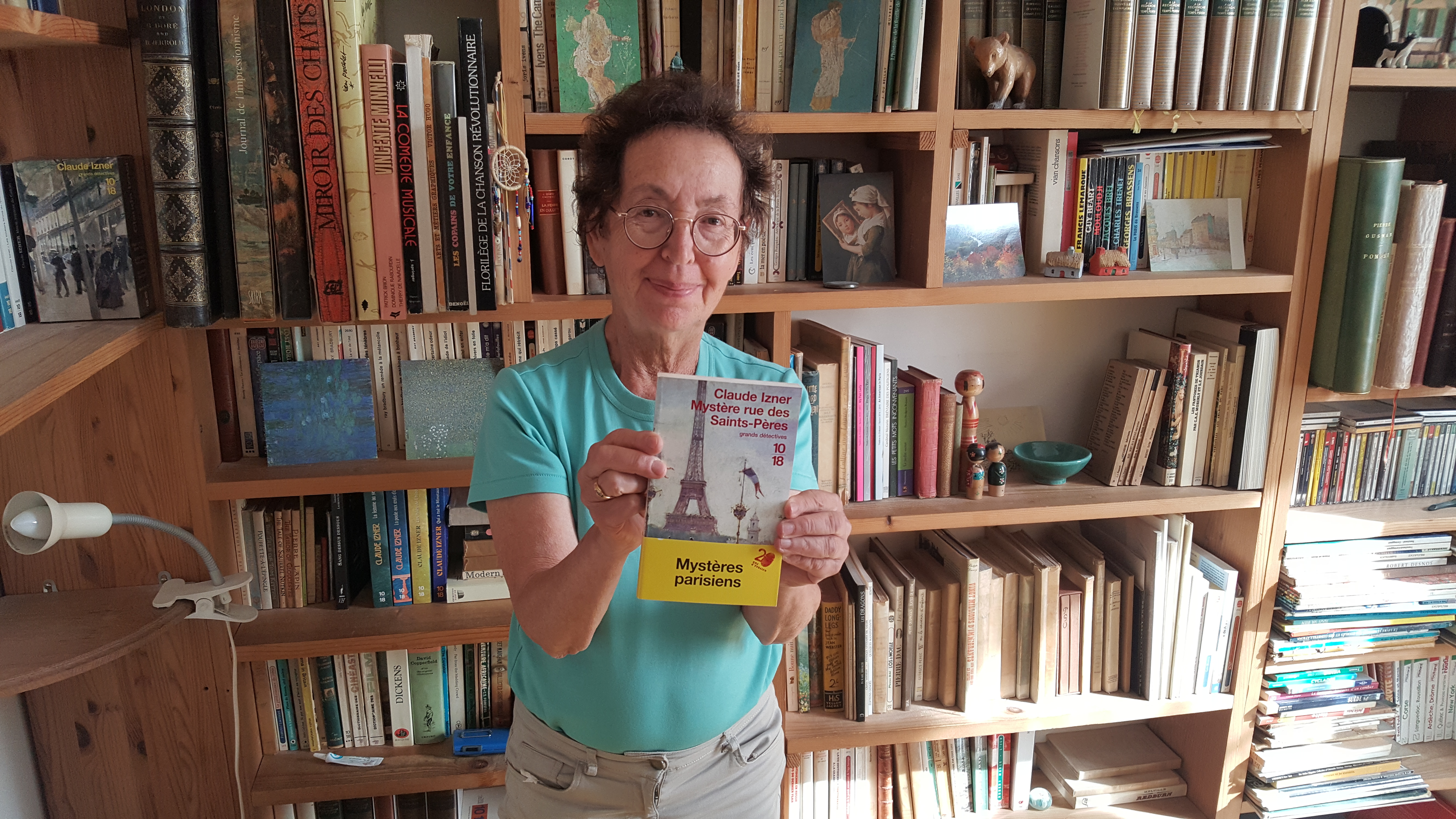

Recently the Ivens Foundation received six reels of a working copy of The 17th Parallel (1968). Laurence Lefèvre gave these reels to André Stufkens in her place in Montreuil. She got this working copy from her sister, the late Liliane Korb, who passed away in 2022. At the age of 26 Liliane Korb edited this long documentary about the peoples war and fight for independence of the Vietnamese people against the US occupation. Previously the Ivens Foundation also received an old print of Borinage from the Limburg Museum.

Liliane Korb

Liliane Korb (1940) made short films herself and edited films of among others Peter Brook, Chris Marker and Joris Ivens. Besides these jobs she was a so-called 'bouquiniste', a book seller at the famous bookstalls near the river Seine. Together with her sister Laurence she wrote under the pseudonym of Claude Izner a successful series of crime stories entitled Les Enquêtes de Victor Legris. The protagonist of these books, Legris, was himself a bookseller / bouquiniste at the end of the 19th century and tried to solve various crimes in Paris. The twelve booktitles reached a sale of 850.000 copies and were translated into English, Spanish, Russian, Italian, Portuguese and Swedish. 'Brilliantly evokes 1890's Paris' wrote The Guardian about the series.

The first part, published in 2003 after indepth research, was called La mystère de la rue des Saints Pères, which refers to the street in Paris where Joris Ivens and Marceline Loridan-Ivens were living. For her Ivens was a kind of mystery, she fell in love with him, but a relationship became impossible after Ivens left to China with Marceline Loridan-Ivens to film the Yukong-sereis. Liliane Korb passed away in 2022 at the age of 82. Laurence Lefèvre stated that she is very happy that she could give this film to the Ivens foundation and is in good hands and care now.

The Ivens foundation is keeping some 270 films of Joris Ivens, mostly nitrate films..

The writer Laurence Lefèvre with the book she wrote together with her sister Liliane Korb, the first part of a series entitled: Mystère rue des Saints-Pères.

Photo by Liliane Korb of Joris Ivens in the rue des Saints-Pères, 1980's. Joris Ivens with Liliane Korb (left) and Maguy Aziari in the editing room of The 17th Parallel.