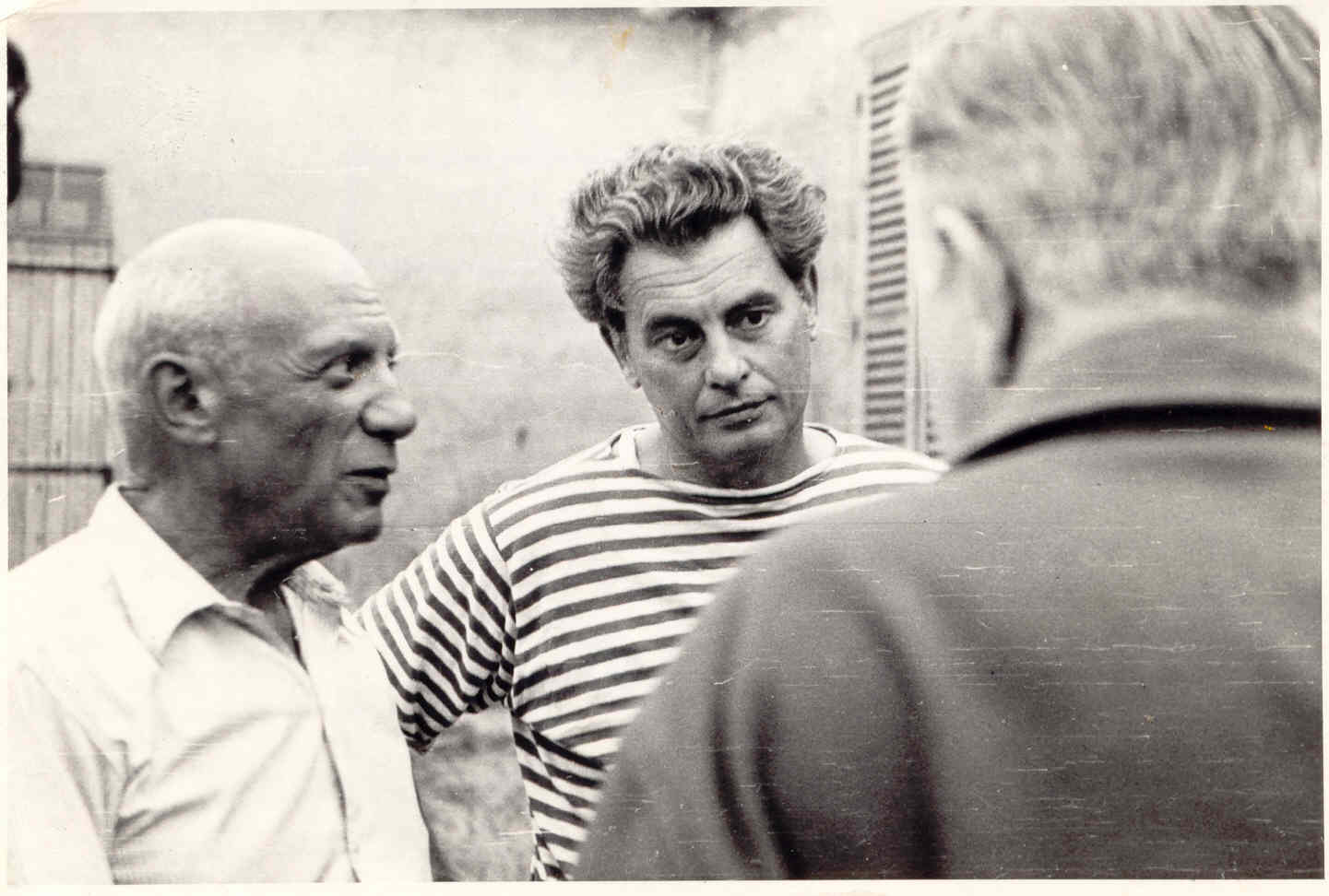

In 1951 Joris Ivens met Pablo Picasso during a visit to his atelier in Vaucluses. Marion Michelle made a series of photos of them, together with poet Jacques Prévert, which are on display at the exhibition about 'Picasso: Shared and Divided' in Museum Ludwig, Cologne (25 September 2021-30 January 2022). After the Second World War Picasso was 'a hero of the left' and used in this way. His dove, symbol for world peace, became a tool for propaganda in the Eastern Bloc. What do we associate with Pablo Picasso today? And what associations with him did the divided German people have in mind during the post-war years, when he was at the height of his fame?

Marion Michelle, Pablo Picasso talking with Joris Ivens and Jacques Prévert in Vaucluses, 1951. Copyright: European Foundation Joris Ivens.

Ivens and Picasso

Joris Ivens met Pablo Picasso in 1951 in Vallauris, together with poet Jacques Prévert. Later on Picasso was asked to design the cover of a book about Ivens’ The Song of the River (1954). How was Pablo Picasso’s work received in a divided postwar Germany? In Museum Ludwig in Cologne a fascinating exhibition presents the answer. A special cabinet shows permantly excerpts from Ivens’ The Song of the Rivers and documents, photos and books present how Picasso made the design, a flower with leaves in the shape of six workers’ hands.

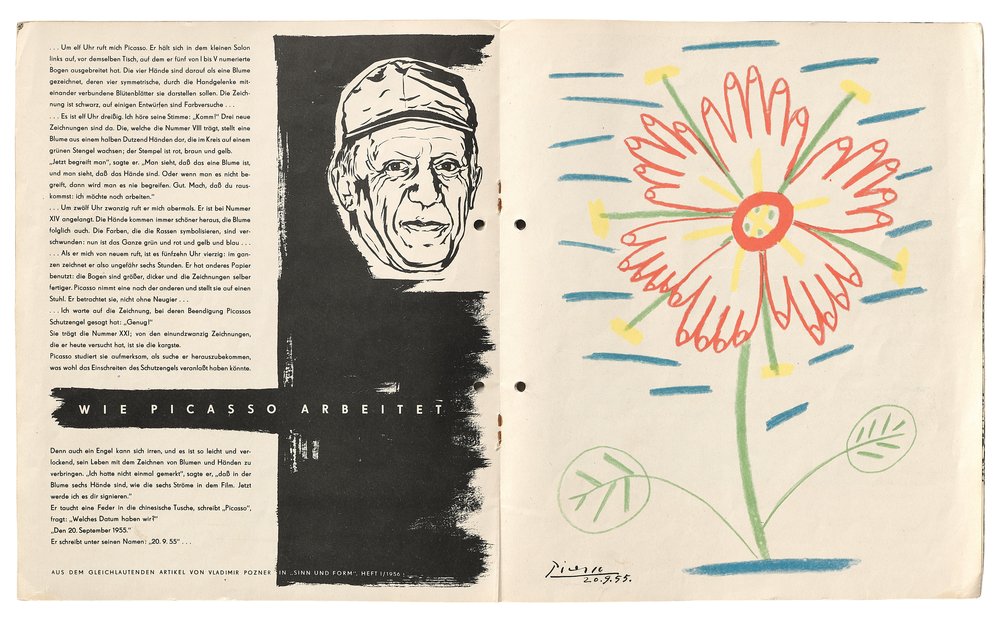

Günter Jordan wrote a chapter ‘Picasso, Ivens, and the GDR’ in the catalogue, in which he unfolds how the design for the film book was created. The Song of the Rivers, to which already artists like Bertolt Brecht, Dmtri Shostakovich and Paul Robeson contributed needed a book with a jacket and an eye catching design . For Ivens only one artist was worthy considering: Picasso. Vladimir Pozner, the script writer, was to arrange this. Pozner had been more or less Picasso’s neighbour in Paris, and set off to Cannes. He explained to Picasso what the film was about and its leitmotiv: workers’ hands, which day after day change the face of the earth and the fate of humanity. When Pozner met Picasso he already had made four sketches of hands shaped in a flower. Half an hour later he presented another three drawings. One drawing after another other its shape becomes more clear and the tension between flower and hands fades away, both aspects attract equal attention. At 12.30 he again made new sketches until 17.40 he was ready with a complete series of 21 proposals of which the last one was the best. In the meanwhile he had added colour to it and asked the date: 20 September 1955. Picasso remarked that only afterwards he noticed that the flower consisted of six leaves. Quite a coincidence: Ivens’ film was about six great rivers and the strength of the workers movement.

Two documents at the exhibition illustrate the creative process:

Letter from Vladimir Pozner to Picasso, June 25, 1955

Dear Comrade,

I know that if you only read all the letters you receive you would not have time to work. I know that everyone who writes to you is asking for something. And I don’t know what else to do but to write to you and ask you for something. It’s an old story. You remember the film I made with Joris Ivens, “The Song of the Rivers,” which you couldn’t see because you had the flu. You were unwisely kind enough to promise to make a poster for this film. In the meantime, “The Song” has had an adventurous life throughout the world, banned in France, butchered in England, shown in Haiphong on the very evening of the Liberation, and in Peking for the anniversary of the Communist Party of China, illegally introduced into colonial countries, where it was screened in small, discreet meetings, and dubbed in 16 languages from Spanish and Arabic to Japanese.

To help it become better known, an album will soon be published, with the participation of those who collaborated on the film, Ivens, Shostakovich, Brecht, Robeson and me, about 300 photos and the commentary text. So, here it is: We are asking you all to agree to make a drawing, a sketch,

whatever you want, for this album, to be placed on the cover. The cover will be made of unbleached canvas. As few or as many colors as you like. No title, as your sketch will be used for different language editions (there will be at least three: French, English, German). Approximate size: 22 × 25 cms. I’m sending you some pictures of the film I have at hand: to give you a poor idea. You know what it is about: the life, misery, and struggles of workers all over the world at mid-century. And the rivers that flow through the film are the Mississippi, the Ganges, the Nile, the Yangtze, the Volga, and the Amazon. It’s a very great work: you would honor us by being associated with it. Please let me know what you decide.

Fraternally yours,

Vlad Pozner

Advertising pamphlet for Lied der Ströme with an excerpt from

Pozner’s text “Wie Picasso arbeitet” (The Way Picasso Works)

. . . Picasso calls me at eleven. He is in the small sitting room on the left, in front of the very table on which he has spread out five sheets, numbered I to V. The four hands are drawn on them as a flower, joined together at the wrists so as to represent their four symmetrical petals. The drawings are in black, but colors have been tried out on a couple of the studies. . . .

It is eleven thirty. I hear his voice: “Come here!” He now has three new drawings there. The one with the number VIII shows a flower made of half a dozen hands growing in a circle on a green stem; the pistil red, brown, and yellow.

“Now you get it,” he says. “You can see that this is a flower, and that those are hands. And if you can’t get that, you never will. Right. Off with you, I must carry on.”

. . . At twelve twenty he calls me again. He has reached number XIV. The hands are becoming increasingly beautiful, and thus the flower as well. The colors symbolizing the races have been dropped: now the whole thing is in green and red and yellow and blue.

. . . When he calls me back again it is fifteen forty: so all in all he’s been drawing for about six hours. He has used different paper: the sheets are larger, thicker, and the drawings themselves more finished. Picasso picks them up one by one and props them up on a chair. He looks at them, not without curiosity.

. . . I’m waiting for the drawing at which Picasso’s guardian angel said,

“Enough!” as he finished it.

It bears the number XXI; of the twenty-one drawings he has attempted today, it is the sparsest. Picasso studies it attentively, as if trying to make out what could have prompted the guardian angel to intervene. Because even angels make mistakes, and it is so easy and tempting to spend one’s life drawing flowers and hands. “I hadn’t even noticed,” he says, “that there are six hands in this flower, like the six streams in the film. Now I’ll sign it for you.”

He dips a quill into the Chinese ink, writes “Picasso,” asks, “What’s the date?”

“The 20th of September 1955”

He writes under his name: “20.9.55

Like many fellow French intellectuals, Picasso joined the Communist Party in 1944. Yet unlike most of them, he never resigned from it until his death in 1973. He put his signature to party appeals, designed posters, donated generously, toasted Stalin on his birthday or portrayed him as a young man (which sparked indignation), and above all he drew countless doves, the Communist symbol of peace. Although he did not like traveling, he went abroad to take part in the meetings of the peace movement. Yet he never came to Germany. The Communist Party was banned in the Federal Republic in 1956. While Picasso’s engagement was regarded there as a fad, he for his own part stressed that politics and art belong together because the artist lives not in art but the world.

Far more than we do: This is the main idea of the exhibition, which reveals a forgotten breadth, tension, and productivity of these appropriations. It deals not only with the artist, but with his audience, which interpreted Picasso’s art in very different ways in the capitalist West and in the socialist East. The German Picasso was divided, but this division also stimulated the reception: Because everyone questioned his art, it had something to say for everyone.

The exhibition features political works, such as the painting Massacre in Korea (1951) from the Musée Picasso in Paris. These are shown alongside some 150 exhibits that reflect the impact of Picasso’s work: exhibition views, posters, catalogues, press reports, letters, files, films, and television reports, as well as a theater curtain from the Berliner Ensemble on which Bertolt Brecht had “the peace dove militant of my brother Picasso” painted.

Picasso served as a figurehead and symbol for both systems and in both German states. He was a member of the French Communist Party and supported struggles for liberation as well as peace conferences. But he lived in the West and allowed bourgeois critics to conventionalize him as an apolitical genius, “the mystery of Picasso.” Which works were shown under socialism, and which under capitalism? How was his work conveyed? Did the West see only the art, and the East his politics? And how did the artist view things himself? Picasso, Shared and Divided examines the image that people took from Picasso’s pictures in the two Germanys. One focus is Peter and Irene Ludwig’s Picasso collection, which remains one of the largest to this day. When the Ludwigs made parts of it available to the GDR, they increased the number of works on view there by several times.

Two new works were commissioned for the exhibition. The exhibition architecture designed by the artist Eran Schaerf links the exhibits without hierarchically structuring artworks and their social use. Wooden installations, diagonal partitions, and the bare museum walls convey the impression of a deliberate incompleteness. Individual exhibits remain embedded in their context, and the way in which we appropriate them remains evident. Peter Nestler’s film Picasso in Vallauris was shot in January 2020 to bring Picasso’s mural War and Peace into the exhibition. The film focuses on Picasso’s production as well as his relationships and political connections, and it looks at the people who live in Vallauris today against this background.

A catalogue will be published in German and English, edited by Julia Friedrich, with texts by Yilmaz Dziewior, Julia Friedrich, Bernard Eisenschitz, Stefan Ripplinger, Hubert Brieden, Georg Seeßlen, Günter Jordan, Iliane Thiemann, Theresa Nisters, Boris Pofalla, Thorsten Schneider, Émilie Bouvard, and Sarah Jonas. Cologne 2021, 248 pages. 266 color illustrations, 22 x 28 cm, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König. 29.80 EUR (retail price), 25 EUR (museum price).

Curated by Julia Friedrich

The website picasso-shared.de offers a digital accompaniment to the exhibition. It will present all the topics from the exhibition with a selection of content. Peter Nestler's film Picasso in Vallauris, which was produced especially for the exhibition, can be viewed here in its entirety.

Download the program to the exhibition here (PDF).

The exhibition received substantial funding from the Peter and Irene Ludwig Foundation, the Kunststiftung NRW, the Ministry of Culture and Science of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia, and the Kulturstiftung der Länder. Additional generous support came from the Freunde des Wallraf-Richartz-Museum und des Museum Ludwig e.V., the REWE Group, and the Berner Group.

The exhibition is organized by Museum Ludwig with the exceptional support of the Musée national Picasso-Paris.