Publiek luistert naar de muziek bij Regen bij de opening op 2 februiari 2014.

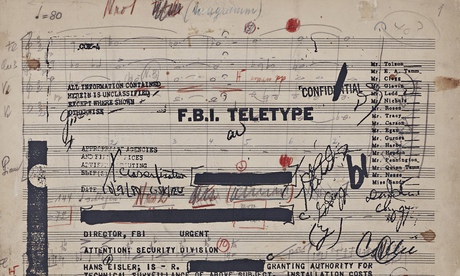

De Schotse kunstenares en Turner Prize winnares Susan Philipsz stelt van 1 februari tot 4 mei 2014 een muzieklandschap tentoon in de Hamburger Bahnhof, het museum voor hedendaagse kunst in Berlijn. De klanken van Hanns Eisler’s muziek Fourteen Ways to describe Rain (1941) bij Ivens’film Regen (1929) zijn te beluisteren in wat ooit de grote hal van het station was. Die hal staat volgens Philipsz voor aankomst- en vertrek, voor afscheid en terugkeer, een melancholisch gevoel dat zij beluisterde in het werk van de Duitse componist enexile Hanns Eisler. De muziek van Ivens’ vriend Eisler wordt in de hal vergezeld door grote zeefdrukken met collages van partituren en bladzijden uit de FBI rapporten. Eisler moest de VS verlaten vanwege communistische activiteiten, hij zou ‘de Karl Marx van de muziek’ zijn. Deze collages doen sterk denken aan de videoinstallatie van Steve McQueen, de maker van 12 Years a Slave, getiteld End Credits, met 6 uur lang de pagina’s uit de FBI-files van een andere vriend van Ivens: Paul Robeson. Een immer actueel onderwerp sinds Edward Snowden laat zien hoe veiligheidsdiensten werken.

Uit The Guardian van 26 februari 2014:

Sound artist Susan Philipsz puts the FBI under surveillance

The `Karl Marx of music` was banned by the Nazis, tapped by the FBI and wrote scores for Charlie Chaplin. In her first major show in Berlin, the Turner prize-winner explores Hanns Eisler`s life, times and suspected crimes

Five-foot-five; weight 175lbs, heavy and with a prominent stomach. Blue-eyed and balding: this is how FBI files describe the composer Hanns Eisler.

Born in Leipzig in 1898, Eisler studied under Arnold Schoenberg and became a friend of Bertolt Brecht. Half Jewish, half Lutheran and a supporter of the German Communist Party, Eisler`s work was banned by the Nazis in 1933 and spent the prewar years travelling through Europe and to Moscow and Mexico, before obtaining a permanent United States visa in 1938. There, he worked first in New York and then Hollywood, before he was suspected of communism and denounced, not least by his sister, who worked for an American intelligence agency. Eisler was derided during his investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee as "the Karl Marx of music" and Hollywood`s top Soviet agent.

Having been blacklisted, Eisler was finally forced to leave the US in 1948, firstly to Austria and then to East Berlin,

How apt to meet him again in a former Berlin railway station, in a sound work and series of large silk-screens by the Glasgow artist Susan Philipsz. A Turner prize winner in 2010, Philipsz has lived in Berlin since 2001. She was awarded an OBE earlier this year.

Part File Score, Philipsz`s first major public show in her adopted city, fills the resounding emptiness of the Hamburger Bahnhof with three of Eisler`s compositions, each performed for two instruments – piano and violin; and cello and trumpet. Her 24-channel installation, in which Eisler`s compositions for films – Prelude in the Form of a Passaciagla, for the 1924 abstract animation Opus 111 by Walter Ruttman; Fourteen Ways to Describe the Rain, for Joris Ivens` 1929 film Rain; andSeptet No 2 for Charlie Chaplin`s 1928 movie The Circus – play one after the other. Eisler had been a student and friend of Schoenberg, and in Philipsz`s work, each part of Eisler`s compositions is recorded separately according to Shoenberg`s 12-tone chromatic scale and relayed through loudspeakers attached to the hall`s 24 supporting pillars.

Glasgow-born, Berlin-based Susan Philipsz`s Part File Score. Photograph: Nick Ash/ Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

A series of large silk-screens on the side walls tells the miserable story of Eisler`s years in America – as recorded in his FBI files. The pages, with all their blacked-out redactions, are printed over the composer`s own annotated musical scores. We get glimpses of his life, times and suspected crimes, as well as his contacts with Schoenberg, Chaplin, "Bert" Brecht (as the files call the exiled German playwright and director), Theodore Adorno (with whom he co-authored Composing for the Films in 1947) and Fritz Lang. There are snatches of Eisler`s own depositions, as well as the details of the cost of his surveillance and phone-tapping. The FBI found nothing.

The sounds echo and strain around the long, arched hall. A Berlin rail terminus until 1848, the Bahnhof was first converted into a transport museum, but since the mid-1990s it has been one of the city`s main contemporary art spaces. I follow the music and lose myself in the notes. A passage begins behind me, then slides here and there in a great unravelling sound that seems to fracture even as it comes together. One note from a speaker nearby, the next from far away. The sound coalesces in space, and never loses its coherence and musicality as the notes attack from different parts of the building, even though one feels that everything is about to fall apart. Standing next to a speaker, one becomes aware of how atomised the music has become, of how important are the gaps, the silences and pauses. Philipsz has turned Eisler`s music into something that sounds almost like an interrogation.

The metaphoric resonances and relationship to Eisler`s fractured life, with its proximities and distances, its lapses and secrets (and who knows what secrets there might have been; the things the FBI never recorded, the things hidden under those felt-tipped redactions), and the sheer strain of keeping his life on track could not be made more clearly. Something similar occurs in Steve McQueen`s 2012 End Credits, which uses Paul Robeson`s FBI files as the basis for a work that tracks the relentless paranoia of state surveillance. Neither McQueen`s nor Philipsz`s works could be more timely.

But the important thing is being here, walking and standing still, listening and looking. The empty space has its own resonances. The mind tries to orchestrate the other people walking, running, lingering. I turn it into choreography.

As the music goes on – there are only the briefest pauses between the three looped compositions – a couple kiss on the huge, empty floor. A woman drapes herself over a bench and appears to sleep, or sink into herself, as her child plays nearby. Someone else patrols the perimeter, doing circuits. The music goes on and on as people come and go.

In the music there is rain, Chaplin caged with a big cat, abstraction. Written for the movies, Eisler`s music is displaced by its context, by time and by our experience of it. Being here is complicated. One also thinks of other works by Philipsz, and in particular of her sound work Study for Strings, the sound amplified at the far end of the railway station platforms in Kassel for the last Documenta exhibition, the music lost in the wind and the noise as one looked across to platform 13, where once the Jews departed, never to return.

But everything returns one way or another. When Philipsz won the

Turner prize I wrote that the way she used space was as important as the music itself. Here, space becomes place. One doesn`t necessarily need to know of Eisler`s personal difficulties to get a sense of Philipsz`s elegiac intent. As much as Part File Score keeps returning to another man`s life and its ambitions, mistakes and travailles, it is hard to be here without thinking of one`s own life, where it might be leading.